Chicago, IL – June 10th – Serpent’s Teeth

Serpent’s Teeth – June 10th – Chicago, IL

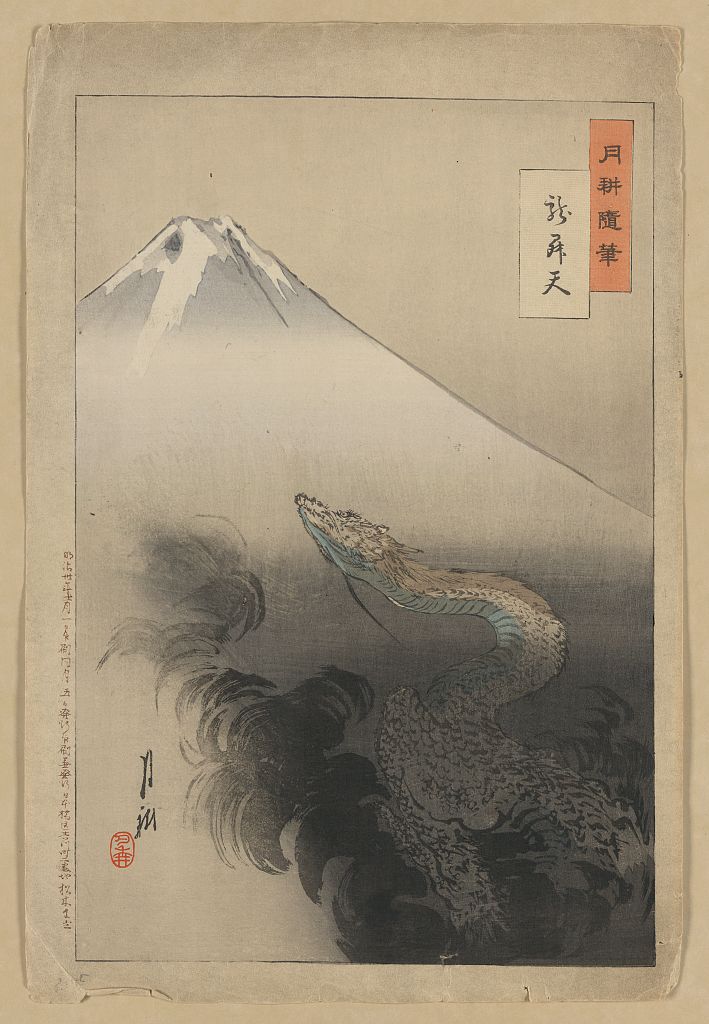

Today’s Drums and Space is inspired by the mysticism of Serpents.

The wall of the drums is serpentine in nature. At times, it feels and sounds like a giant sea creature navigating the open seas. The rhythm begins and moves through it, bringing life across the giant nest of acoustic and electric drumheads. It is all connected- pulsing through and guiding a path forward. This movement is similarly related to the ground we stand on today.

Chicago, the home of the winding Chicago River, where riverboats once plied the waters- bringing music born from New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta up north. This great serpentine river is responsible for the journey that created American music, the beast that is Rock and Roll.

Tonight, we embody the spirit of the serpent both through the wall of drums and through the manifestation of that journey.

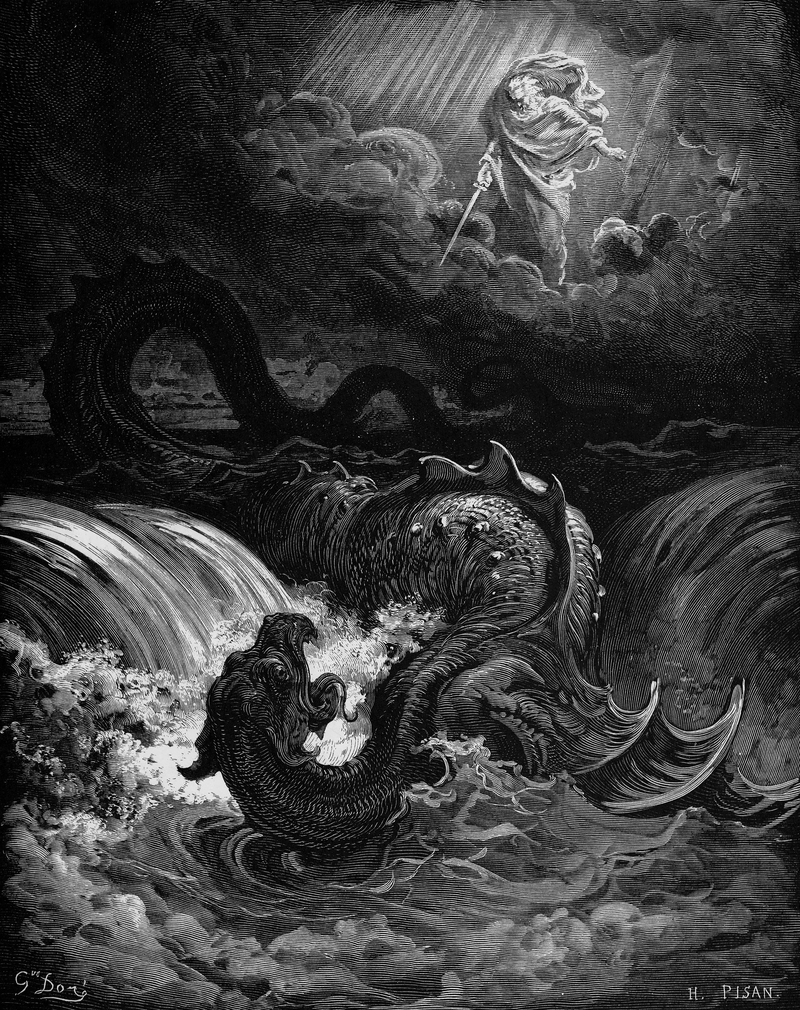

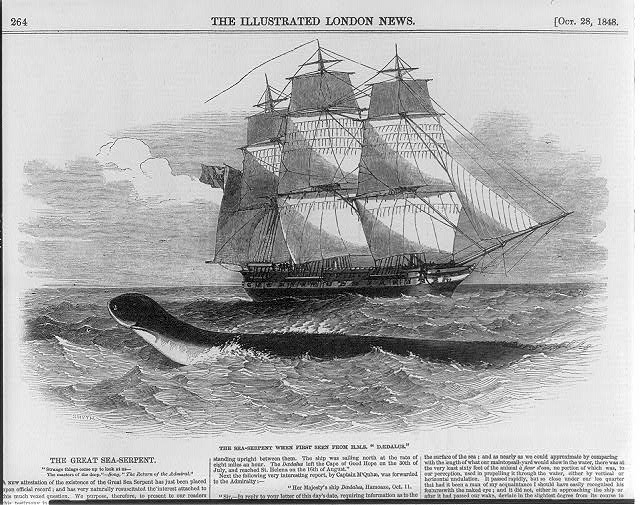

The sea serpent is a mythological and legendary marine animal that traditionally resembles an enormous snake. The belief in huge creatures that inhabited the deep was widespread throughout the ancient world. A large number of the well-authenticated stories of monstrous marine creatures seem to be explicable as incorrect observations of animals already well known.

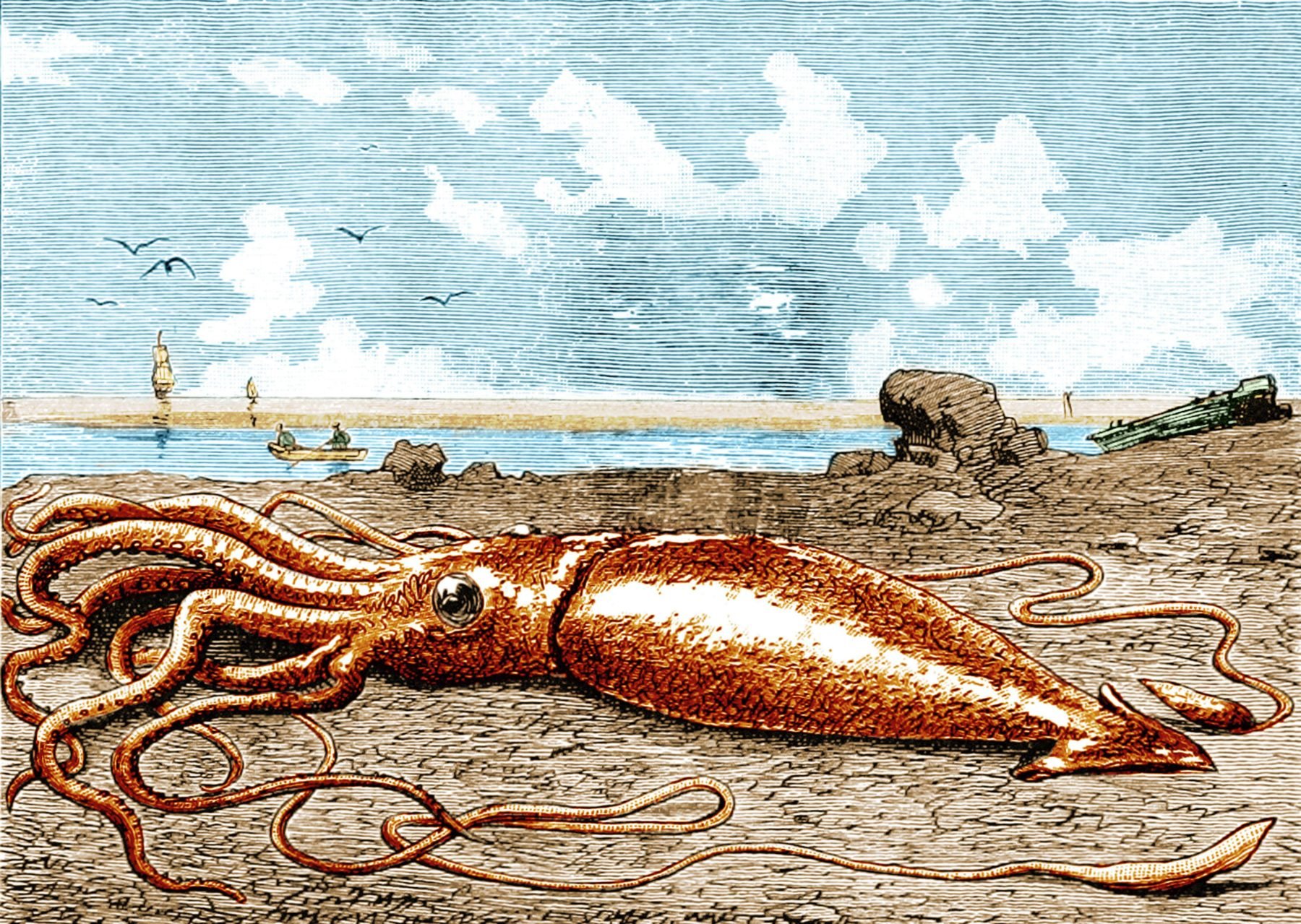

Giant squids (Architeuthis species) are presumably the foundation on which many accounts are based; these animals, which may attain a total length of 50 feet (15 metres), occasionally frequent the regions from which many accounts of sea serpents have come. One of these animals swimming at the surface with two enormously elongate arms trailing along through the water would produce almost exactly the picture that many of the strangely consistent independent accounts require: a general cylindrical shape with a flattened head, appendages on the head and neck, a dark color on top and a lighter shade beneath, progression steady and uniform, body straight but capable of being bent, and spouting water.

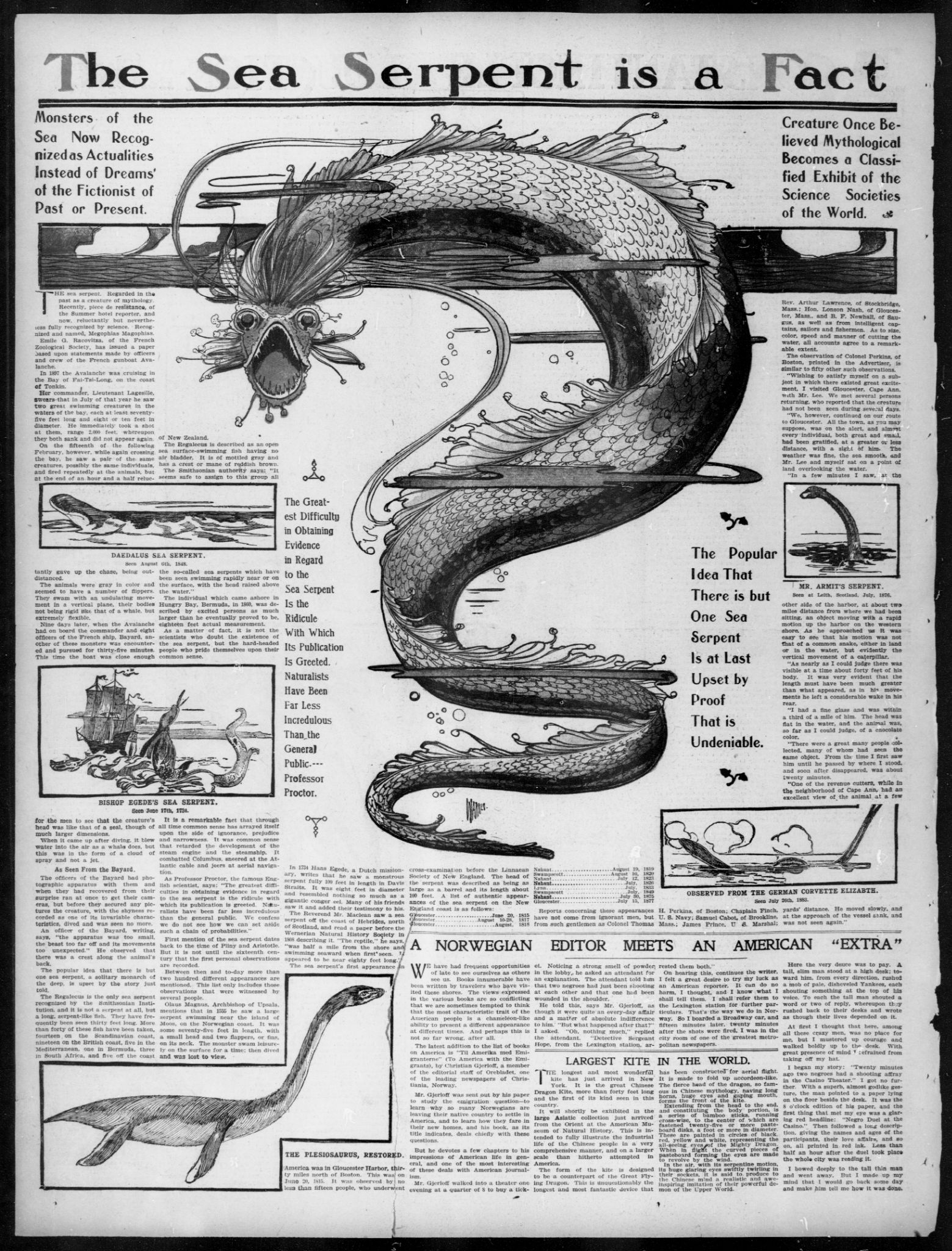

Beginning with a sighting of the Gloucester, Massachusetts sea serpent in August 1817, the idea arose that there was a sea serpent found in the Atlantic off North and South America. Gloucester legends had told of a strange monster on the coast from colonial times. An 1817 report of the Linnaean Society of Massachusetts summarized interviews with people who had seen it, including sightings from previous years. They proposed that it was a new species, Scoliophis atlanticus.[2] It was said to be a dark sinuous animal that moved vertically up and down in the water like a caterpillar. But actual reports of observers varied a great deal. Witnesses on the shore said it resembled a long line of barrels, riding high in the water. Those who saw it from ships reported a snake that was dark with a head like a horse. Subsequent drawings of it varied a good deal. Captain Joesph Woodward of the schooner Adamant reported an encounter off the coast of Cape Ann in May, 1818. He said he shot a cannon at the monster. He was quoted as saying that after the cannon shot:

The serpent shook its head and its tail in an extraordinary manner and advanced toward the ship with open jaws; I had caused the cannon to be reloaded, but he had come so near that all the crew were seized with terror, and we thought only of getting out of his way. He almost touched the vessel and, had I not tacked as I did, he would certainly have come on board. He dived, but in a moment we saw him come up again with his head on one side of the vessel and his tail on the other as if he was going to lift up and upset us. However we did not feel any shock. He remained five hours near us, only going backward and forward.

— British Literary Gazette, August 1, 1818 (page 489)

Part of the excitement in the 1800s about the monsters of the sea was the idea that science could now explain what had once been myth and legend. Many attempts were made to explain the Gloucester serpent as a group of migrating whales or seals. Some proposed that an animal thought to be extinct might still be alive, such as long-necked ocean dinosaurs. People at the time assumed that there was just one “great American sea serpent.” But it is quite possible that the variety in the descriptions means that there was not one animal (or group of animals) but various accounts of different creatures or other natural phenomena. The other underlying assumption common to many sea serpent stories of this period, which is also found in Captain Woodward’s account, is that it was necessary to try to kill the animal. The concept of sea serpents as creatures that would attack boats and kill sailors continued to color people’s perceptions.

In January 1860, another face was given to the sea serpent, as an astonishing animal washed up on Hungary Bay in Bermuda. It is, in fact, a recognizable species, the giant oarfish or ribbon fish. Even today, news stories about encounters with giant oarfish often call them “the real sea serpents.” Unlike most fish, they do not have scales. Their dorsal fin and sensory organs that spring as hair-like filaments from its head, are bright red. Two red oar-shaped sensory organs also grow from it’s pectoral muscles, giving it its name. It is thought to be the longest bony fish with well-documented specimens about thirty feet long and some longer reported. Historic sightings of sea serpents with red manes might well have been sightings of this unusual fish. They are deep water animals of warm seas and are rarely sighted except when they are dying or dead.

There are discoveries to be made in the ocean still, particularly in the deep ocean. There may be species of animals once described as sea serpents that have not been discovered yet. The true sea snakes seem to be moving northward with warmer waters so that they are being encountered by people who have never seen them before. Three yellow-bellied sea snakes washed up dead on southern beaches in California in 2015 and 2016, far north of their normal range. If you should see something strange in the ocean, appreciate it from a safe distance, and remember the long tradition of sea serpents that has been carried by humans wherever they travel on, in, or near the sea.

Sources:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/sea-serpent

https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2016/08/great-american-sea-serpent/